Cold. OHMYGOSH can Zimbabwe get cold. I think often as Americans we think of Africa as one country – one hot, dry, wild animal filled country. It’s not. It’s an entire continent. And just as it’s rare to find wild animals roaming freely across the land, they are in protected game parks, in the winter Zimbabwe is cold. It blows all of those preconceptions about hot and dry out of the water… so to speak. In addition to having their own climate, each of these countries also has it’s own culture and personality. And perhaps nowhere was that more apparent for us than Zimbabwe.

Zimbabwe’s personality was first evident in people’s names. While there are the occasional John, Mary, and Peter, most people had very different names. Some of our favorites? Simba – which doesn’t mean lion in the Shona language; it means strong. Other fun names? Absolute, Jealous, and Obvious… because why shouldn’t they be names? And then there’s Mitchell. Mitchell sounds like a perfectly normal name, right? And it is – except that it’s pronounced Michelle and it’s the name a lovely baby girl. It’s just that no one knows that you don’t spell Michelle with a “T.” Mitchell’s mother says her daughter’s name is Mitchell – like Mrs. Obama.

Zimbabwe’s personality was first evident in people’s names. While there are the occasional John, Mary, and Peter, most people had very different names. Some of our favorites? Simba – which doesn’t mean lion in the Shona language; it means strong. Other fun names? Absolute, Jealous, and Obvious… because why shouldn’t they be names? And then there’s Mitchell. Mitchell sounds like a perfectly normal name, right? And it is – except that it’s pronounced Michelle and it’s the name a lovely baby girl. It’s just that no one knows that you don’t spell Michelle with a “T.” Mitchell’s mother says her daughter’s name is Mitchell – like Mrs. Obama.

Maria and I came to Zimbabwe with a mission. We wanted to scope out a second site in Africa for global health trips. Zimbabwe had a few things going for it: 1) it uses English language and US dollar; 2) we have an established relationship with the Zimbabwe Artists Project; and 3) it’s got great vacation spots like Victoria Falls and game parks – places that we could take students to unwind after intense medical days in the villages. However, when we’re considering global health sites, we have to take many things into consideration, including safety, cost and accessibility of food and housing, how well established collaborating organizations are, and other various factors. Thus, an in-person trip is important to check things out.

As I mentioned, we are working with ZAP. Zimbabwe Artists Project (ZAP) is a non-profit in Portland that was established by a Lewis & Clark College professor, Dick Adams. He had been taking Lewis & Clark students to Zimbabwe and discovered that there was a whole genre of art being produced in this little village in Zimbabwe called Weya. The Weya artists told stories with paint, tapestry, or cloth. To get to Weya, you drive two hours on paved road, and then turn left onto dirt road and go another two hours to the end of the road. And there, in the middle of desert-like farmland is an oasis of artists. Needless to say, the market for art in Weya is slim; so Dick started ZAP to help the artists sell their art, in order to pay for education and health care. Maria and I both sit on the board of ZAP.

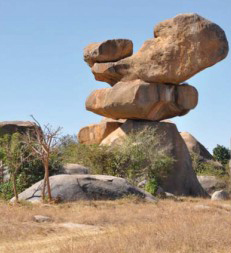

ZAP’s executive director, Theresa, and in-country program manager, John, hosted us in Zimbabwe. They picked us up in Harare, and brought us to Weya. The drive was beautiful – past huge boulders balancing on each other, and miles upon miles of savannah. John explained to us that the village of Weya is so remote that the road isn’t on the map. This creates a problem. The government won’t maintain any road that isn’t on the map. But a road can’t go on the map unless it’s well maintained. Thus, if you don’t have a good road, you will never have a good road. TIA. At this point, the road is barely passable. But no one in the village has a vehicle anyway, so it doesn’t matter. John said that often the ZAP jeep is the only car on the road.

ZAP’s executive director, Theresa, and in-country program manager, John, hosted us in Zimbabwe. They picked us up in Harare, and brought us to Weya. The drive was beautiful – past huge boulders balancing on each other, and miles upon miles of savannah. John explained to us that the village of Weya is so remote that the road isn’t on the map. This creates a problem. The government won’t maintain any road that isn’t on the map. But a road can’t go on the map unless it’s well maintained. Thus, if you don’t have a good road, you will never have a good road. TIA. At this point, the road is barely passable. But no one in the village has a vehicle anyway, so it doesn’t matter. John said that often the ZAP jeep is the only car on the road.

John was a fantastic tour guide for our trip. He pointed out landmarks, and shared historical facts about Zimbabwe. As a white native Zimbabwean, John’s life hasn’t been easy. In 2000, white people were forced out of Zimbabwe, and now John is part of 1 percent of the population left who is white. He has people shout at him on the street to, “go home.” But of course, he IS home. He was born in Zimbabwe and has lived there most of his life.

When we arrived in Weya, we went straight to the clinic to check it out. The clinic serves an area of around 10 square miles, or maybe 15… It’s hard to say. Now, that may not seem like a large area, but imagine being sick and having to walk up to 10 miles to get care. Most of us, when we’re sick, don’t even want to walk from the car to the clinic. Suddenly the reality of how remote it is makes more sense, right? The clinic is a cement building with a men’s ward (i.e., a cement room with four beds in it for men), a women’s ward, a pre-natal ward, a birthing room, an outpatient visit room, a room for family planning, a room for immunizations and weighing babies, and a room for storing pharmaceuticals. There’s also a small kitchen and the ‘sister’s’ office. The ‘sister’ is the nurse who runs the clinic. It’s quite small for serving such a large area.

When we arrived in Weya, we went straight to the clinic to check it out. The clinic serves an area of around 10 square miles, or maybe 15… It’s hard to say. Now, that may not seem like a large area, but imagine being sick and having to walk up to 10 miles to get care. Most of us, when we’re sick, don’t even want to walk from the car to the clinic. Suddenly the reality of how remote it is makes more sense, right? The clinic is a cement building with a men’s ward (i.e., a cement room with four beds in it for men), a women’s ward, a pre-natal ward, a birthing room, an outpatient visit room, a room for family planning, a room for immunizations and weighing babies, and a room for storing pharmaceuticals. There’s also a small kitchen and the ‘sister’s’ office. The ‘sister’ is the nurse who runs the clinic. It’s quite small for serving such a large area.

We spent quite a while talking to the sister, trying to determine the similarities and differences with Tanzanian rural health clinics. There were a lot of similarities. Like Tanzania, the Weya clinic is exceedingly short of supplies – everything from gloves and syringes, to infant heaters for premature babies, and scales to measure people’s weight. However the clinic is also lacking basic supplies like sheets for the hospital beds, and mops and cleanser for the floor, and notebook paper to make medical records. They don’t have anything.

Of course, the biggest shortage was medicine. The storeroom for pharmaceuticals is near empty. There was one bottle left of worm medicine (albendazole). The shelves for TB meds (antibiotics) were bare, as were all shelves for hypertension, diabetes, etc. There were a few boxes of anti-malarial medicine – mostly because it’s now winter and its not malaria season. However, HIV meds? There were dozens of cases of HIV meds – stacked to the ceiling! That was an enormous surprise and a big difference from Tanzania who can’t get HIV meds or any others. And then the sister told us that most of them HIV meds are arriving expired. So they have medicine, but it might not work.

Of course, the biggest shortage was medicine. The storeroom for pharmaceuticals is near empty. There was one bottle left of worm medicine (albendazole). The shelves for TB meds (antibiotics) were bare, as were all shelves for hypertension, diabetes, etc. There were a few boxes of anti-malarial medicine – mostly because it’s now winter and its not malaria season. However, HIV meds? There were dozens of cases of HIV meds – stacked to the ceiling! That was an enormous surprise and a big difference from Tanzania who can’t get HIV meds or any others. And then the sister told us that most of them HIV meds are arriving expired. So they have medicine, but it might not work.

Like in Tanzania, women will be tested for HIV, but men resist it. The rate of HIV in Zimbabwe overall is around 20 percent, and is higher in the villages. The sister told us that lately she’s seen more men coming in – and it happens when their wives bring home a negative test. Then the men will come in because they figure that if their wife is negative, they’re negative too. Otherwise men won’t come in unless they’re on their deathbed, and their wives are wheeling them in a wheel barrow. Imagine hauling your spouse in a wheel barrow for several miles… Ugh! The life expectancy for people in Zimbabwe is about 58 years – so 20 years less than an American, but only two years less than Tanzanian.

Rosalyn and her baby daughter, Mitchell, invited us to stay with her for the night. Rosalyn has a farm with chickens, cows, and a field of tobacco (yes, tobacco farming is big in these parts). However, Rosalyn’s husband had a stroke last year, so right now, he’s living in Harare, and her farm isn’t operating at full capacity. There’s no indoor plumbing, but she does have a well. And there are his’ and her’s latrines not too far from the home. At one time, the farm had electricity. You can tell because there are ceiling lamps and she owns a 1980s style stereo with a cassette deck. But there’s no electricity now. Apparently, many years ago, somewhere in the community electrical grid, someone didn’t pay a bill. And then a transformer was struck by lightening. And when ZESA, the electric company, came to fix the power, they decided not to fix it for an entire section of the community because of that one unpaid bill… Or that’s how the story goes.

With no electricity in Weya, star gazing is fantastic at Rosalyn’s place. We sat on the front stoop and watched the stars as Rosalyn and her cousin cooked dinner – beans, bitter greens, and sadza. Sadza is a corn porridge that is as thick as paste, and is a staple of Zimbabwean food. We’ve had it before in Tanzania where it’s called ugali. Unfortunately, there’s no nutritional value in the porridge at all. But it’s cheap to make and it fills the belly. Most Zimbabweans will get meat to eat once a week if they’re lucky. Otherwise, its cheaper to eat vegetarian. That said – they aren’t eating vegetables. It’s beans and sudza – pretty much for every meal.

Food preparation happens in a separate ‘kitchen hut’ – which is a round room with a grass roof and no chimney. There’s a fire in the center of the room, and the women cook over the fire –as the room progressively fills with more and more smoke. Maria and I couldn’t even enter the room because the smoke was so thick. My eyes watered and Maria’s tongue swelled – and neither of us could breathe. Rosalyn laughed at us, and said that she’d serve dinner in the house rather than in the kitchen where they usually eat.

Food preparation happens in a separate ‘kitchen hut’ – which is a round room with a grass roof and no chimney. There’s a fire in the center of the room, and the women cook over the fire –as the room progressively fills with more and more smoke. Maria and I couldn’t even enter the room because the smoke was so thick. My eyes watered and Maria’s tongue swelled – and neither of us could breathe. Rosalyn laughed at us, and said that she’d serve dinner in the house rather than in the kitchen where they usually eat.

There’s not much to do after dinner in a powerless village, and it’s cold. So we all crashed where we could huddle under thick blankets for the night.

The next morning, Maria and I met with the village leaders to talk about our global health program and assess their desire to have us there. One of the leaders walked over to the school and got one of the teachers to come participate in the meeting because the teacher could write and take notes whereas the four elders could not. These leaders are not chiefs – they’re elected leaders – and they range in age from 20-something to 70. They were great, charismatic men… and I swear one of them was a doppleganger for NBA star Chris Bosch of the Miami Heat.

The next morning, Maria and I met with the village leaders to talk about our global health program and assess their desire to have us there. One of the leaders walked over to the school and got one of the teachers to come participate in the meeting because the teacher could write and take notes whereas the four elders could not. These leaders are not chiefs – they’re elected leaders – and they range in age from 20-something to 70. They were great, charismatic men… and I swear one of them was a doppleganger for NBA star Chris Bosch of the Miami Heat.

We talked for about two hours, exchanging information about the health of the community, natural medicine, education, and anything else they wanted to talk about. They were very excited to learn of the medicinal properties of some of their plants, like the Meringa tree. One of the leaders immediately pounced on the idea of planting more Meringa trees and exporting teas made with it. They complained about the distance from the clinic for most of the people in the village, and came up with a simple solution – a town ambulance. Now it will be raising funds for a vehicle. In the end, they invited us to come back and bring students. We will maintain the relationship through the teacher, and through John (of ZAP).

We also met with the village midwives. There are two, and they are very important women. While the government has now proclaimed that all women should be having their babies at clinics, in villages like Weya, it’s often not possible to get to a clinic for a birth. Thus, these two midwives deliver many of the babies in the village. One of the midwives was trained in the more traditional ‘apprenticeship’ model, and she is now training her daughters to be midwives. The other midwife was trained at the clinic. Like the clinic, the midwives lack gloves – and this is a severe issue in a country riddled with HIV. I truly wish there were a good way to get everyone gloves!

Finished in the village, we headed back to Harare – thinking our work in Zimbabwe was complete. However, one should never think that when traveling with Maria or me. Our guest house in Harare was called Jacana Gardens (and I highly recommend it if you’re headed to Zimbabwe.) As it turned out, the owners of Jacana Gardens (Rian and Wellen) are a Dutch couple who worked for Doctors Without Borders for 20 years. They wound up in Harare to treat a cholera epidemic about 10 years ago, and never left. They retired, bought a house to convert into a guest house, and stayed. Rian is an amazing women – so welcoming and helpful. I think she’ll be a great contact for us for the future. What’s even more amazing is that Rian has decorated the guest house with art from Weya artists – so she’s a great contact for ZAP too.

Finished in the village, we headed back to Harare – thinking our work in Zimbabwe was complete. However, one should never think that when traveling with Maria or me. Our guest house in Harare was called Jacana Gardens (and I highly recommend it if you’re headed to Zimbabwe.) As it turned out, the owners of Jacana Gardens (Rian and Wellen) are a Dutch couple who worked for Doctors Without Borders for 20 years. They wound up in Harare to treat a cholera epidemic about 10 years ago, and never left. They retired, bought a house to convert into a guest house, and stayed. Rian is an amazing women – so welcoming and helpful. I think she’ll be a great contact for us for the future. What’s even more amazing is that Rian has decorated the guest house with art from Weya artists – so she’s a great contact for ZAP too.

One last note on Zimbabwe – and that’s about the food. It was the best of food, it was the worst of food. We had the best food we’ve had in Africa in Zimbabwe, at a little shopping center in Harare. The restaurant, called Pistachios, is a little Italian café/coffee shop. They had carrot, date, pineapple muffins, butternut squash coconut milk soup, bacon, feta, basil, tomato muffins, focaccia with pesto and parmesan… If we’d spent more time in Harare, I think we could have easily eaten there every day. That was is stark contrast to the village food. Lunch with the leaders was… interesting. There was a choice, day-glow bologna on white bread, or a fishy concoction. Maria opted for the neon pink bologna, and I went for the fish, which turned out to be canned cat food. (Maria spotted the can after lunch.) Both of us got sick. And yes, I can confirm that my cat food meal was truly the worst food I’ve had in Africa. You’ll notice that I buried this at the end of a long letter. I expect that most people don’t even read to the end of my letters, so maybe I won’t get a lot of flack for eating cat food…

All in all, our trip to Zimbabwe was great. We are excited to move forward with establishing a global health site there, though it will likely take a few years to make things happen. As they say in Tanzania, pole pole (slowly slowly)…

Love to all!

Heather