In the fall of 1956, five students and a group of determined naturopathic doctors set out to start a school and save a profession.

(Editors Note): Many alumni refer to it as National or simply NCNM. Today’s students playfully refer to what’s now National University of Natural Medicine as Hogwarts, with a nod to Harry Potter. But across the country, alumni and others call it The Mothership for the role the school played in bringing the naturopathic profession back from the brink of extinction, and the role it continues to play in health care. Join us as we step back in time to look at the struggles to establish the college and its tumultuous passage to become a university.

It was a time of revolutionary technological change that would, in turn, help fuel sweeping social changes in the decades to follow: the dawn of television, rock and roll, and widespread use of “wonder drugs” like penicillin and the polio vaccine.

It was the time of the Hungarian Revolution, when students with few weapons beyond rocks and Molotov cocktails temporarily cast off the yoke of Soviet dictatorship. It was also the beginning of the Space Age with the launch of the Sputnik satellite and the start of the race to the moon.

And on May 28, 1956, three naturopathic doctors, Frank Spaulding, Charles R. Stone and W. Martin Bleything filed articles of incorporation with the state of Oregon to mark the birth of National College of Naturopathic Medicine. Theirs was a revolutionary act too, essentially the culmination of a long, harrowing battle stretching back to 1880s Germany. The naturopathic idea that nature is the primary source of health and healing—whether through good food, medicinal herbs, or the healing properties of water, countered the mechanistic version of medicine then gaining precedence in the Western world.

From the beginning of its introduction to America by Dr. Benedict Lust in 1900, naturopathy, along with chiropractic, herbal and other natural medicine practices, faced sometimes violent opposition from the medical establishment. Still, by the 1930s, by some estimates there were thousands of naturopathic doctors and some 50 schools teaching various forms of natural medicine in the U.S. and Canada.

Perfect Storm

World War II, and the postwar boom years that followed, brought together currents that nearly doomed naturopathic medicine in North America. One factor was the emergence of seemingly miraculous drugs that enabled patients to find quick solutions for their ailments. No one knew that microbes would eventually develop resistance to these emerging drug therapies. Another factor, according to former NCNM President Guru Sandesh Singh Khalsa, ND (’78), involved the deaths of several of the leading doctors who had founded naturopathic colleges. Dr. Khalsa, whose paper, commissioned by NCNM, “The History of the National College of Naturopathic Medicine,” details the early years of the college from 1956 to 1980, said infighting between naturopathic associations, as well as tensions between naturopathic doctors, chiropractic doctors and their professional associations, played a key role. “The profession literally had one foot on the banana peel,” he said.

Another major cause of the crisis was the continuing impact of The Flexner Report, which had been commissioned in 1908 by the Carnegie Foundation at the request of the American Medical Association. Its survey of the 155 medical schools then established in North America found all but a handful of the schools substandard, including most of the historically black colleges and all of the naturopathic or chiropractic schools. It recommended that for-profit or “proprietary” schools, then the model for most alternative medical training, be closed or merged with colleges and universities.

While the report recommended positive changes such as a strong emphasis on bioscience and increased education before and after medical school, it also recommended schools make extensive investments in laboratories and research facilities, which few of the smaller schools could afford. Flexner also listed all alternative and complementary modalities as “sect” medicine based on pseudoscience and recommended schools who taught such medicine be closed. The report’s conclusions and recommendations were widely adopted by licensing and accrediting bodies across the U.S., resulting in the closure of many schools of medicine. “They wanted to get rid of all these pesky people who didn’t fit the mold,” said Khalsa. “They raised the bar and then made sure we (NDs) didn’t reach the bar.” Basically, he said, “What they set out to do was crush us.”

The impact of the report on the healthcare system was profound. According to a 2003 article in the Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons, “The Impact of The Flexner Report on the Fate of Medical Schools in North America After 1909,” in 1904 there were 160 MD granting institutions educating more than 28,000 students. By 1920, there were only 85 MD granting institutions and 13,000 students. Another consequence was the closure of all but two African-American medical schools. As a result, few doctors of color were being produced. Also, the new scarcity of medical school slots contributed to the reemergence of nearly all-male student bodies.

Similarly, by the early 1950s, naturopathic colleges in the U.S. and Canada were few, and producing only a handful of graduates. By 1955, there was only one college in North America still teaching naturopathic medicine, Western States College (Western) in Portland, Oregon—and it was on the ropes.

Chiropractors and Naturopaths

Ironically, adoption of one of The Flexner Report’s recommendations, to require two years of college-level coursework as a prerequisite to admission, contributed to a steep drop in Western’s enrollment. According to the school’s official history, Western (now known as University of Western States) adopted the two-year requirement as a quality measure, but most other chiropractic schools did not follow suit. Many students passed up Western to attend schools with less stringent admissions requirements. As a result, in 1955, Western’s enrollment and tuition tumbled and the school, unable to pay its bills, was on the brink of closure.

Western’s board held a series of urgent meetings and called on its alumni, including its naturopathic graduates, for help. According to the school’s board minutes, a handful, including naturopathic/chiropractic physicians Stone, Bleything, Spaulding and Dr. Henry N. Merritt attended. The naturopaths, already stung by lack of representation on the board and rumors that had circulated for a year that the school would soon drop its naturopathic program, demanded board seats and a guarantee that the program would continue before they would offer financial help. Initially, they got both, with a bylaws change that would expand the board to include naturopathic representation. But the Western board reversed itself two months later over concerns about the legality of the bylaws amendment and a letter from the National Council on Education that affirmed earlier communications that it would revoke accreditation if the school continued to offer its naturopathic program. Western would survive after a board member remortgaged his house and took out a life insurance policy naming the school as beneficiary, but the naturopaths were out in the cold.

Hello, Hawthorne

According to a 1981 recording of recollections from Dr. Joseph Boucher (pronounced boo-shay), a Canadian ND and founding faculty member, “We all realized that before too long naturopathy would be dead in the water, because with no new graduates, no one could take our places as we moved off the scene. It was only a matter of time.” Boucher said the executives of naturopathic organizations from Washington, Oregon and British Columbia held a joint meeting in 1956 and “resolved to form a committee and endeavor to obtain a charter for a new college.” As Spaulding later said, the feeling was, “This medicine is too important for there not to be a college of naturopathic medicine.”

They decided to establish a school in Oregon due to its existing licensing law dating to 1927, which included a broad scope of practice. Recalled Boucher: “A bill was steered through Salem in record time. Someone said they had never seen a bill move so quickly to grant the charter for the national college. So here we were with a new infant dumped in our laps and no maternal milk to nourish it.”

The doctors were dispatched to beat the bushes wherever they could to raise money for the endeavor. Spaulding traversed the country in a Chrysler he borrowed from brother-in-law Dr. Ken Peterson, a 1951 ND/DC graduate of Western States and a founding faculty member. According to an interview with Dr. Peterson conducted by Dr. Sussanna Czeranko at the NorthWest Naturopathic Physicians Convention in 2010, Spaulding visited NDs across the country to gather some $100,000 in cash and pledges.

Dr. Gerald Farnsworth, an NCNM founding board member and early faculty member, told Czeranko that Seattle and British Columbia NDs would drive to Portland each Friday in order to teach classes. “It was very difficult,” Farnsworth said of the early years. “I lived a 16-hour drive away from Portland (in Kamloops, B.C.) and when we had a meeting once, or sometimes twice a month, I was out of my office a great deal.” He recalled that there were no airline connections at the time, no divided highways, “and an awful lot of gravel roads full of potholes. So it was very stressful, but very necessary.”

By July 1956, the three founding physicians and others who worked to establish the school huddled in an old house on Southeast Hawthorne plotting revolution—or put another way, working out the details to govern a new school that they hoped would save the profession. After furnace problems in the house cropped up, the group moved a couple of blocks away to a rented storefront at 1931 SE Hawthorne Blvd.

The original course catalog, a 29-page typewritten manuscript covering the years 1956–1958, outlined the naturopathic philosophy; admissions requirements (a high school diploma plus two years of college) and graduation requirements; the four-year course curriculum; student conduct guidelines; and fees. Tuition was $450 per year, with an anticipated total of $1,800 for the four years, plus lab, equipment and other fees. The catalog mentions a clinic, though it’s not clear if it was at the Hawthorne site or shared among the working naturopaths. According to the catalog: “Clinics are in continuous operation and treatment is available. These clinics are fully equipped for instructional purposes and serve the profession in every phase of clinical and diagnostic work.”

The catalog also lists Florence E. Johnston, ND, as librarian and states that the college had 5,000 volumes and periodicals. The original NCNM classroom building on Hawthorne is today a café listed by the city of Portland at 9,460 square feet. The catalog indicates that the same group who argued unsuccessfully with their Western States alma mater to retain its naturopathic curriculum, played key roles in the school’s early years. Dr. Spaulding was the first board chair, joining Drs. Stone and Bleything on the founding board, while Dr. Merritt served as the first president.

From the beginning, women played key roles at NCNM. Besides Dr. Johnston, who doubled as the X-ray technician, the catalog lists Elizabeth Murray as the administration’s comptroller, and Dr. Dorothy Johnstone, a naturopathic physician, as a faculty member. Dr. Johnstone was also a founding board member. In all, the new school had five professors, 22 assistant professors, an X-ray technician, clinic/lab tech and a librarian—none paid.

According to Boucher, “Everybody pitched in and began to decorate, renovate and so forth.” NCNM opened its doors for the first time at 8 a.m. on Sept. 4, 1956. There were five students, four postgraduate chiropractors seeking ND degrees, and one true first-year, Ivor Morris, who also took care of maintenance and facilities. According to the Old Farmer’s Almanac, the day was clear and a warm 81 degrees. Morris eventually dropped out due to illness, but three students received the first ND degrees issued by the college in 1957: Linwood M. Fulcher, George A. Adams and William R. McNabb. Andrew E. Kabanuk followed in 1959.

The Faithful Few

In 1958, the college moved to a large house at 2625 SE Hawthorne, which had long been used as offices by naturopathic doctors. For the next several years, NCNM continued scraping by with little money and about five students per year. Tuition did not cover expenses, so the college limped along largely from the pocketbooks of the faculty and administration. “It really was a tremendous struggle, with lots of blood, sweat and tears to keep it going,” recalled Boucher. “No one drew one penny either in expense money or salary. Every penny that came in from tuition and from donations was used to pay the rent, the utilities or whatever expenses were necessary…all the teaching and the janitor work and the building maintenance was done by the faithful few that tried to keep it alive…somehow, when it seemed it couldn’t go on another month or so, somehow it kept going.”

In 1959, the college faced the first of many crossroads that tested the founding group’s resolve to continue. Boucher recalls that burnout, particularly among the Oregon doctors who spent many hours at the school away from their practices, had set in, and despite the formation of an NCNM Boosters Club by Dr. Walter Adams to wring a few dollars for the operation from patients, friends and physicians, money was tight. “Finally, it came to a point where it looked as if NCNM would have to fold.”

However, said Boucher, “Then Dr. (Harry) Bonnelle, who was one of the very active naturopathic physicians and who had a fair-sized clinic in Seattle, said ‘No, we can’t let that happen.’’’ Though the charter needed to stay in Oregon, it allowed for branches anywhere, said Boucher. “Dr. Bonnelle said ‘Why don’t we move the few students that we have up there to my clinic?’ There were many more doctors in Seattle in the field willing to teach in the evening. This gave NCNM a sort of shot in the arm.”

So, the four-year program was moved to Dr. Bonnelle’s two-story building at 1327 North 45th Street in Seattle. Downstairs was used for classes and a clinic, while upstairs had apartments used by students. When enrollment began to climb in the 1970s, the second floor was converted into class space, with the entire first floor taken up by an expanded clinic. Headquarters during this period were in the office of Dr. John Noble at 2627 North Lombard, Portland, where Noble continued the ND program for chiropractors.

When Bonnelle died a few years after classes began in Seattle, his widow offered the college first option on purchasing the building. With little money in the school coffers, nine naturopaths formed the NCNM College Corporation, each contributing $1,000. With those funds, the Seattle building was purchased, the first owned by NCNM.

In a 2016 interview, the late Betty Radelet, ND (’68), NCNM’s first female graduate, recalled a small, but collegial Seattle group in those days. She said no one gave her any grief about being the only woman in the program. “My classmates were very helpful,” she recalled. Of course Dr. Radelet, who practiced until she was 89, already had a chiropractic doctoral degree, and was the single mother of seven children. In short, she wasn’t someone to trifle with.

The college’s early curriculum emphasized basic sciences like anatomy, physiology and chemistry for the first two years, then more advanced science, increasing lab and clinic time. In the final semesters, the focus was on hydrology, minor surgery and a heavy dose of naturopathic philosophy and techniques. With such small classes, students enjoyed strong mentoring from faculty members who were practicing physicians, including training in some of their specialties.

For instance, Radelet recalled, Boucher wanted to hypnotize her as part of a class demonstration at the Seattle branch. She was reluctant, but finally agreed, and went into a trance. She said Boucher gave her a post-hypnotic suggestion for sleep, which she used the rest of her life.

Kansas

From 1956 to 1973, a total of 29 graduates received ND degrees from NCNM. With the dawn of the 70s though, and increased interest in all things “alternative,” the numbers began to climb. The period from 1973 to 1979 saw a total of 110 graduates. The class of 1972 alone had 30 students, after graduating only one student the year before.

With more students, but still little cash, the college faced a dilemma—how to accommodate them. With the Seattle branch at near capacity, and lacking a science laboratory and enough classrooms, NCNM inked a cooperative agreement in 1973 for basic sciences to be taught at Portland’s Warner Pacific College, a conservative private Christian college. The agreement lasted only a term, dissolving over philosophical differences.

About that same time, a chance meeting in an unlikely venue led to the college moving first- and second-year basic sciences to the Midwest. NCNM Board Member Dr. Robert Broadwell, who was practicing in Kansas at the time and owned a cattle ranch there, was attending a cattle auction in Emporia when he happened to strike up a conversation with a gentleman at the event. The man was Ronald Ebberts, president of the College of Emporia.

Emporia was a small, struggling school that needed new students. It also had modern science facilities and an experienced full-time science faculty. A deal was struck and in fall 1973, 20 first-year students found their way to yet another new NCNM location. The students completed a term there and dispersed for home during the holiday break, only to learn that the college had closed its doors. However, a similar agreement was negotiated with Kansas Newman College, a Catholic school located 50 miles south in Wichita. As head of the Kansas program, Broadwell, as he had done at Emporia, welcomed 20 new first-years in early 1974 to go along with the 20 second-year students, an unheard number for NCNM at the time.

Bill Tribe, former alumni officer and interim NCNM president from 1979–1980, was a student during the Kansas years. He recalled a dedicated, eclectic and close-knit student group. “There was so much passion and energy. Everyone was so welcoming and we all had this feeling that we had found our place in the world,” he said. “One of the things that made NCNM exciting to me was the many different paths people took to bring them there.” Some students came with knowledge of meditation and herbs. There were different religions and lifestyles represented. “The students hung out together to study, play, live and learn from each other,” he said.

Kansas was quite a culture shock for most of the students, especially those from one of the two coasts, said Tribe. The geography was flat and relatively featureless, and the people politically conservative. While the townspeople in Wichita were friendly, he recalls students, some with long hair and beards, being quizzed about their studies and their religious beliefs. On campus at the parochial school, the NCNM students felt a bit isolated and mainly stayed in the science building, where they enjoyed the excellent lab facilities and instruction from the Kansas Newman College faculty, a handful of Kansas NDs and Broadwell.

Broadwell, now in his 90s, recalled that the Kansas branch was focused on strengthening what he felt was weak training in the basic sciences and in clinical diagnostics. His World War II experience, in which he received minimal medical training and then was handed a lead medical role to tend to soldiers assigned to amphibious landing craft, colored his view of education going forward. Basically, he wanted to make sure his students had solid experience in laboratory testing and diagnosis, and a thorough understanding of human anatomy, physiology and pathology. After World War II, he noted, few American hospitals and fewer colleges had clinical lab facilities. Oregon and Washington schools certainly did not, he said. But at both the College of Emporia and Kansas Newman College, “We had adequate facilities to get into all those things.”

Bruce Canvasser, ND (’77), said of Broadwell: “He was tough, but in such a way that we admired him. We were kind of in awe. When he said ‘Cut your beards, we’re going down to the Kansas Legislature,’ we were there.” Dr. Canvasser said the students deeply respected Broadwell’s knowledge of homeopathy, pathology and basic sciences. “I have the feeling that a lot of us would not have continued in natural medicine without Dr. Broadwell.”

Back to Portland

By 1975, NCNM was at a crossroads. It was operating three branches in three states, all on a proverbial shoestring. Although the board had discussed an East Coast clinical studies branch to make the school truly national, that never materialized. The Kansas program, meanwhile, had a cohort of about 20 students who had finished their two-year basic sciences studies and were ready to move on to clinical training and the core naturopathic curriculum. Kansas had never been intended to be the site of the final two years, and without a naturopathic licensing law in the state, it was felt that there were not enough NDs to oversee clinical training.

In Seattle, where students were still studying for the final two years, there was no room for more students and no money for expansion. Also, Washington’s licensing law did not allow for teaching the full range of modalities in the clinic that Oregon law accommodated. So, while about 30 students began basic sciences training that fall at Kansas Newman College, the group that began studies at the College of Emporia packed up a rental truck and headed back to Portland.

A new college had emerged and survived in large part due to the sheer determination of its founders. In the Portland years that followed, a true institution of higher learning emerged, but not without many more challenges.

Postal In Portland

In 1975, NCNM rented space in downtown Portland, with an eye toward consolidating all operations there. Located at 510 SW Third Avenue, the four-story building was built in 1900 as the Postal Telegraph Building. Dr. Stone, one of the original founders, had his offices there for many years. Bill Tribe recalled that the core faculty in those days consisted of a few new grads and a few of the older doctors. Enrollment averaged about 35 students during those years. The school started with several larger rooms on the second floor, but eventually expanded to include most of the third and fourth floors.

Tribe and others said the Postal Building space initially needed a lot of work, so everyone pitched in with carpentry and painting, even plumbing, to create classrooms, a clinic and a lab, the latter two guided by Broadwell. Still, Tribe said, even when completed, the spaces were less than ideal: The school received complaints that partially naked patients could be seen through the windows, and there was sometimes a temporary evacuation due to fumes and odors emanating from the lab. Also, since exam room partitions did not go all the way to the ceiling, doctor-patient conversations in these pre-HIPAA days were not as private as one would have preferred.

Even so, “It looked like an old-time doctor’s office,” with marble floors and walls in some areas, recalled Canvasser, who finished his final two years there and then became the clinic director. “We had a nice little clinic room, waiting room and a big pharmacy of homeopathic remedies and herbs.” He said the curriculum, both at Kansas and in Portland was very challenging, leaving little time for much beyond studying. Though finances were tight, he credits Drs. Boucher, Joe Pizzorno and John Bastyr with supporting student academic and clinical needs as much as possible.

Not everyone was happy about the situation, though. The college faced a near revolt when tuition more than doubled to $1,500 a year in order to afford the new clinic in Portland. “Students were really upset,” said Khalsa, but were calmed by a talk from Bastyr, who had become president in 1976.

Khalsa, who finished his final two years as a student in the Postal Building, recalled a colorful, if noisy environment in his historical paper. Construction noise and sirens from the street were a constant. Students could often hear the “tink, tink,” of jewelers working down the hall, and the sound of electric guitars from the ground-floor music store often mixed with the lectures. There was a greasy spoon restaurant on the ground floor too, which added an avocado sandwich “for your health” specifically for the naturopathic students. Third Avenue in those days was lined with pawnshops, dubbed “the Financial Aid Office” by students. Parking was always an issue too, he said, which the city enforced every day at 4 p.m. An announcement on the college intercom system would remind people of the arrival of meter readers. More than once, he said, patients dressed only in exam gowns dashed for the street to plug their meters.

In 1977 the decision was made to close the Seattle branch. Doctors who had invested $1,000 each in the corporation to buy the Seattle building donated their shares to NCNM, which sold the building. The following year Kansas Newman College was notified that NCNM would not renew its contract. The board felt it was important to reunify the college in Portland where the naturopathic community was growing and Postal Building facilities allowed for expansion.

The Great Lock Out

According to the Khalsa history, during the 1978–79 school year, a group of naturopathic physicians complained to the board of directors about concerns over the curriculum and the direction of the college. The group further alleged misconduct and irregularities by some members of the NCNM administration. The administrators denied the allegations, but the board ordered the locks to the main doors changed and appointed a new administration.

In response, much of the faculty, especially the new basic sciences faculty and younger instructors, plus students and some members of the board, staged a strike in support of the administrators and refused to attend classes. The conflict threatened the very existence of the school, but after a month of investigations and discussions, the strike ended and the original administration returned.

There was serious damage to the unity of the college, wrote Khalsa, similar to the infighting within the profession itself at some points in its history. Whether the direct result of the conflict or not, most of the remaining long-term members of the board stepped down within a year’s time, including Farnsworth and Dr. Robert Fleming. Bastyr stepped down as president, and was honored with emeritus status. Among the positives during this period was the appointment of the first full-time president, at the recommendation of the administration. Dr. Jan Harris, who was previously an anatomy professor, was the first female president of the college, taking the reins for the 1980–81 school year. About this time too, the board, which had been filled exclusively with naturopathic doctors, began to admit public members, in part to align with state and federal higher education guidelines.

Wrote Khalsa: “By 1980 it was apparent that the National College of Naturopathic Medicine had fulfilled the hopes of its founders to help save naturopathic medical education, and the profession itself, from dying. The future for naturopathy appeared much brighter than it had 25 years earlier. Graduates of the college were creating a renaissance for naturopathic medicine and would soon begin to have an impact on health care in the United States and Canada.”

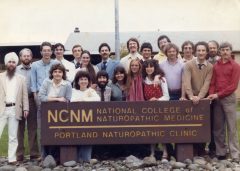

Market Street: First Real Campus

In 1981, with the Postal Building at capacity, the college purchased the former Portland Christian High School campus at 11231 SE Market Street in Portland, just east of Interstate 205. The first true campus for NCNM included seven acres of grounds, a gym, outdoor track, classrooms, a clinic and a library. Classes and the administration relocated to the site for the 1981–82 school year.

In 1981, with the Postal Building at capacity, the college purchased the former Portland Christian High School campus at 11231 SE Market Street in Portland, just east of Interstate 205. The first true campus for NCNM included seven acres of grounds, a gym, outdoor track, classrooms, a clinic and a library. Classes and the administration relocated to the site for the 1981–82 school year.

Recalled Tribe, the move “Helped us become known as a college… It was much better than the Postal Building, there was more room and it was a lot more modern and attractive.” Quite a bit of construction was done on the building, he said, and portable classrooms were brought in to house the clinic.

“It felt like an old grade school with a big track and open space in the back,” said Mitch Stargrove, ND (’88), “I guess one could call it cute in both its smallness and authenticity.”

A big part of that authentic feeling came from the people, said Dr. Stargrove. “At the time, NCNM was a small and personable thing because everyone was in one hallway. So if you needed to talk to a dean or the president, all you needed to do was walk down the hall and you would run into most everybody, and people were generally open and responsive to change.” One was also likely to run into a flying leather hacky sack, a popular activity in the halls at the time, he said.

Friedhelm Kirchfeld, the long-time NCNM librarian who retired in 2006 and died in 2011, was one of the people Stargrove remembers most from the Market Street days. “He was a special character who was an institution unto himself.” Kirchfeld oversaw a cache of rare books that eventually became the largest collection of naturopathic medicine texts in the world. In addition, said Stargrove, “He was always a great resource and a font of knowledge.”

Laurie Regan, PhD, ND (’97), now dean of NUNM’s College of Classical Chinese Medicine, spent most of her time in the naturopathic program at Market Street in just one classroom—Room 101. She recalls, “There were teeny, little elementary school desks where the seat is attached to the desk,” and bathroom facilities sized for children. A few classes were held in the dimly lit gym, which she remembers also housed the food service. From time to time the gym’s ceiling panels would come loose and fall, a hazard everyone watched for. The college’s cadaver lab was in a trailer behind the building, but lacked ventilation, she said, so “we had to wear suits and gas masks” in order to be in there. “I have some notebooks from those days that still smell like formaldehyde.”

In spite of, or perhaps because of the limitations of the old school, Dr. Regan said her class of about 50 students, large in comparison to previous years, was a close-knit group. Regan, who came to NCNM for its focus on homeopathy, but also studied qigong, said many of her classmates went on to play key teaching or administrative roles at the college in the years ahead. “You could call it Yuan Fen,” she said, “a kind of karmic destiny or synchronicity.”

A College Emerges

After all the struggle to found and then maintain the fledgling college, other elements came together in the Market Street years from 1981 to 1995 that transformed NCNM into a true higher education institution. While some alumni still volunteered or taught for little money, the emergence of full-time paid faculty, which began in the Seattle and Postal Building years, became standard at Market Street. A professional faculty, coupled with baby steps toward better facilities, in turn fueled the drive toward accreditation and further legitimacy as a medical college. The college received formal permission in 1981 from the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Committee, a predecessor of the Oregon Office of Degree Authorization, to grant the Doctor of Naturopathic Medicine degree. Candidacy status from the Council on Naturopathic Medical Education (CNME) followed in 1987, with full accreditation coming from CNME in April 1991. According to Laurie McGrath, longtime director of institutional research and compliance, accreditation led to eligibility to receive federal financial aid, which in turn sparked further enrollment growth. Student demographics also began to shift during the Market Street years from a male-majority to a female-majority student body, a trend that continues today.

Another key development in these years was the founding of NCNM’s community clinics. In 1992, after observing a low-income mother struggling with four young children entering the campus clinic, Chris Meletis, ND (’92), worked with administration, faculty members and students to launch NCNM’s first community clinic at the Native American Rehabilitation Association (NARA). The idea was to create a healthcare safety-net for low-income and underserved populations while providing students invaluable experience working with patients. By 1994, NCNM had established a clinic at Mt. Olivet Baptist Church in Northeast Portland, serving a mostly African-American population. A string of clinics at Portland Community College (PCC) sites followed in 1996 along with a clinic in downtown Portland at Outside In, which serves homeless and street youth.

Jill Sanders, ND (’95), who managed NCNM’s naturopathic Natural Health Center on First Avenue before she was named chief medical officer and dean of clinical operations from 2010 to 2014, was a student at Market Street beginning in 1991. Dr. Sanders recalls a close-knit community that warmly welcomed each new class. “It was kind of idyllic. We had such a small community. We had the resources we needed and we had amazing instructors that were so dedicated to the profession, like Tori Hudson, ND (’84); Jared Zeff, ND (’75); and Anna MacIntosh, ND (’89).” Sanders said the growth of the community clinic system to include ever more diverse patient populations was a major factor in the growth and quality of the school’s curriculum. The Outside In experience was particularly valuable, she said, because students and doctors saw far more acute conditions there than they saw at the Natural Health Center, the Pettygrove Clinic or the community clinics.

“In our little 120-person school, we barely did two clinic shifts and didn’t even see patients until after noon when classes were out.” Leaky roofs and cramped spaces characterized the Market Street clinic, she said, and though a better building, the first standalone clinic at First Avenue was also cramped. Sanders noted that the later construction and launch of the campus NCNM Clinic in 2009, which she supervised, was a remarkable change of pace in a relatively short time. Consolidating operations to a modern and spacious building on campus was huge, she said, as was continual quality improvements that resulted in the designation of the NCNM Clinic by the Oregon Health Authority in 2015 as a Patient-Centered Primary Care Home (PCPCH). “Going from that small place to where we are now is mind boggling,” said Sanders.

Despite the gains and growing community visibility and impact, NCNM’s old nemesis, money, often raised its head and roared during the Market Street years. Stargrove also remembers “a low overhead operation” with a small staff and faculty. Still, the financial situation could often be described as “precarious,” he said. “I watched a few times when it skated to the edge.”

Tribe and others credit Dr. James Miller, who was named NCNM president in 1989 and served until 1993, as a steadying force. Dr. Miller had experience with crisis. As president of Pacific University, he guided the Forest Grove, Oregon, school through the aftermath of a devastating fire that destroyed the main administration building in 1975.

More Yuan Fen: Chinese Medicine

The Market Street campus these days is an alternative school called Fir Ridge, part of the David Douglas School District. Little of what alumni remember remains, as the old building was replaced in 2003 with a brand new structure. Visitors to the campus or the steady stream of drivers flowing by on Market Street see little evidence a naturopathic college was ever there. There is even less indication that thousands of miles from its origins in China, the revival of an ancient form of its medicine, now known as classical Chinese medicine, began there.

According to Stargrove, Chinese medicine was taught at the college beginning in 1983 with Satya Ambrose, ND (’89), MAcOM, teaching courses while still a student. About the same time, Dr. Ambrose and Eric Stephens, DAOM, founded the Oregon College of Oriental Medicine (OCOM). The pair rented offices from NCNM and taught NCNM students in the evening. With the arrival of Heiner Fruehauf, PhD, to begin a new classical Chinese medicine program in 1993, OCOM moved to its first campus down the street.

Dr. Fruehauf comes from a family of German physicians who practiced various forms of natural medicine. His great-grandfather, a shoemaker, worked with naturopathic pioneer Father Sebastian Kneipp on the development of sandals intended to promote health, a kind of early Birkenstock. Still, Fruehauf came to Chinese medicine in a roundabout way, initially focusing on European literature and Chinese studies. While working toward a PhD in East Asian Languages and Civilization at the University of Chicago (which he completed in 1990), he was diagnosed with testicular cancer. After discussing options with doctors, family and friends, he had surgery but refused radiation, chemotherapy or drugs. Instead, he traveled to China, experienced the healing power of its medicine, studied with master scholar/physicians, and began a lifelong fascination with the country’s original medical texts.

However, there was a problem. During Chinese leader Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution of 1966–76, the official teaching of Chinese medicine, which became known as Traditional Chinese Medicine, moved away from the ancient master/ student lineage system. The new approach, designed to imitate Western medicine, is devoid of its spiritual elements, and according to Fruehauf and other advocates of the ancient traditions, “severely undermines the energy-based diagnostic and therapeutic mode of thinking that accounts for its holistic nature.” The ancient or “classical” approach is timeless, he said, in that it is “the truth about nature and the universe, and the human body.” Eager to share his emerging knowledge of the medicine, Fruehauf looked to the United States. After considering Colorado and Hawaii, friends told Fruehauf and his wife Sheron about Portland. “They said it was beautiful and they are your kind of people,” he recalled. “We had never heard about it at the time, but eventually everything fell into place. Even on the way from the airport, we looked at each other and said this is going to be it.”

Fruehauf worked closely with Academic Dean Jared Zeff, ND (’79), and administrators Laurie McGrath and Andrea Smith, EdD (former NCNM provost and now vice president of Institutional Research, Assessment and Compliance), on the development of a new classically based program. The idea was to build a curriculum that not only trained ND students in classical Chinese medicine, but one that would pass muster with national accreditors and eventually stand alone. “I personally wasn’t inclined to do some sort of short cut,” said Fruehauf, “politically it was not a good thing to do, because as a naturopathic school we would be eyed suspiciously by the national (accrediting) body. My recommendation was not to do less, but more than what other colleges were doing.”

President Miller and the board agreed and core classes began within the naturopathic program in 1993, with a full curriculum of classical Chinese medicine electives established in 1995. At first, Fruehauf taught all the classes himself, but as student interest grew, he soon found that unsustainable. Fortunately, he was able to hire some of the best and brightest scholars and teachers from Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, where he had done considerable research.

Although classes in Chinese medicine had been a requirement of the ND program, the MSOM degree had historically been added on to the third year of the naturopathic doctoral program for those students who were interested. In 1996, work began to create a master’s program that would focus more on classical training and gain approval of the Accreditation Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (ACAOM), the national accreditors. Working with McGrath, Smith and Sister Mary Dernovek (a consultant with Solutions for Nonprofits), Fruehauf set out to create “a longer and more rigorous program than virtually anyone else.”

“We earned high regard from ACAOM and other professional associations,” said Fruehauf. ACAOM granted candidacy status to the MSOM program in 1998. That same year four students received the first MSOM (offered within the ND degree program) at commencement, with full accreditation following in 2000. In the intervening years, work has continued to refine and grow the program. In 2004, Dr. Laurie Regan returned to the college after seven years in private practice to revise the MSOM curriculum to better reflect classical Chinese philosophy. A Master of Acupuncture program was added in 2008. Then, after many years of diligent work, the school received approval for a Doctor of Science in Oriental Medicine (DSOM) program in 2015 from the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities.

On To Ross Island/Lair Hill

The year 1996, the school’s 40th, was one of the most volatile and important in NCNM history. Three different presidents served the college that year, with the board finally settling on the former president of the Oklahoma College of Osteopathic Medicine and Surgery, Dr. Clyde Jensen, in June.

Jensen recalls immediately having two big tasks. NCNM once again found itself out of space and was anticipating a large incoming class that fall—it was time to move from the Market Street location. The other was a “show cause” letter from accreditors threatening sanctions, including the potential loss of accreditation. Losing accreditation would have meant the loss of federal student financial aid, a killer for most schools.

Jensen, who hadn’t yet relocated from Oklahoma, remembers signing the purchase agreement for the new campus on one of his visits to Portland. Jensen and the college leadership chose a former Portland Public Schools elementary school building named after Josiah Failing, an early Portland businessman, education advocate and the city’s fourth mayor.

Built in 1912, the 60,000 square-foot building was already a part of Portland educational history as the site of the first Portland Community College (PCC) location in 1961, later renamed the PCC Ross Island Center. In 1996, PCC sold the building to Portland businessman and philanthropist Bill Naito. After Naito’s sudden death, the H. Naito Corporation sold the iconic building to NCNM in September 1996.

Its location in the historic Lair Hill neighborhood, south of downtown Portland and near the west end of the Ross Island Bridge, is much closer to transportation, academic and business hubs than Market Street had been. Also, proximity to Portland State University and Oregon Health & Science University made the new campus particularly attractive, said Jensen, because of the potential for collaboration with the two larger schools.

But the first issue to tackle was the accreditation matter. Dr. Smith, having left NCNM during a period of financial turmoil and working now as an accreditation consultant, was brought back in to help deal with the situation. The potential sanctions, she said, were the result of a poor self-study written during the administrative upheaval. Once things quieted down, she said, a good, fully participatory study was done and accreditors were satisfied.

“I never felt that the college was in serious jeopardy,” said Jensen. “It just needed some calm leadership that would create confidence…that they could upright the ship…Once we were able to straighten out some of the internal turmoil, then our ability to recruit students was greatly enhanced.”

Another crisis averted, NCNM readied for one of its largest cohorts ever, well over 100 in the fall of 1996. Fortunately, the old three-story brick school building, with 22 classrooms, an auditorium and library, was, unlike previous locations, not only spacious, but pretty much move-in ready. For the most part, the building needed just a bit of paint here and there, said Jensen.

At Century’s Turn

For a time NCNM continued to run some operations at Market Street. The teaching clinic remained there until 2001, when clinic operations were moved and divided between the Natural Health Center on Southwest First Avenue and the Pettygrove Clinic in Northwest Portland, the latter focused on Chinese medicine. The class of 1997, which had opted to stay at Market Street for classes rather than move to Lair Hill, was the last to study there.

As a new century opened, the college was riding a wave of prosperity it had never experienced before. The school had its largest student enrollment on record in 2000 with 156 students. This was followed up in 2001 with the largest graduating class (126) in school history up to that point. With increased tuition dollars, NCNM looked to its Lair Hill neighborhood, leasing the clinic building on Southwest First Avenue and a portion of the old Oregon Public Broadcasting building at 2828 SW Naito, today’s Administration Building.

“We gradually renovated the substandard areas (of all campus buildings) as we acquired the funds,” said Jensen, while looking to purchase or lease additional space nearby.

In 2001, President Jensen stepped down, having fulfilled his five-year commitment to the school. Much was accomplished during his tenure, but left undone was a potential merger with a larger public school as he had done in Oklahoma. Jensen had been in talks with Portland State University officials, but simply ran out of time to get the merger done. “It presented a scenario that would have been very attractive to both institutions,” he said. “Some on the (NCNM) board wanted to do it, but others were apprehensive. The next administration was not interested or didn’t see the wisdom of becoming part of a public institution.”

The next administration was decidedly short, with new President Dennis Robbins leaving after about a year. NCNM historian Guru Sandesh Singh Khalsa, ND (’78), who later became president of Boucher Institute of Naturopathic Medicine, was appointed interim president, and was immediately beset with a new financial crisis in 2002 when enrollment took a sudden dip and other anticipated revenue failed to materialize. Faced with a $1.4 million deficit, he said, “We had to let people go and had to cut to the bone.”

By the time President William Keppler, PhD, arrived in late 2002, it was almost too late. The former dean of the College of Health at Florida International University (FIU) in Miami, had barely warmed his seat in the President’s Office when he received a certified letter and then a phone call from the U.S. Department of Education. NCNM’s solvency ratio, a measure of cash on hand, assets and financial investments was well below the government’s passing grade. Dr. Keppler and the school had 30 days to come up with $618,000 in cash or face the loss of federal financial aid. “We had 30 days to do that or we would no longer have student financial aid checks coming, and essentially the institution would have to close its doors.”

Keppler, who as the first dean of the health college at FIU had hired 200 faculty members and worked to accredit several different academic departments, had never faced a situation like the one he found himself in. He called an all-campus meeting in the Great Hall (now Bill Mitchell Hall) of the Academic Building. “I invited everybody and closed the door. I said, ‘Look, we can make an effort to raise the $618,000. If we do that, we will go for institutional accreditation the following year.’” NCNM had long been accredited by the naturopathic accrediting body, but had never qualified for the tougher standards from the regional Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities (NWCCU), the West Coast’s main higher education accreditation body via the U.S. Department of Education.

Keppler personally responded to the situation by paying himself one dollar a month for his first three months, and half of his regular salary after that. Hearing that, he said, three faculty members stepped forward and offered to remortgage their homes to raise the funds. “I decided not to accept that. I didn’t want any faculty member to do that.” Instead, with the enthusiastic backing of the faculty, staff and students, Keppler set out with Board Chair Scott South and they helped raise the money “from several sources,” 72 hours before the government deadline.

Then as promised, Keppler, a former evaluator for NWCCU, huddled with faculty and staff to produce a self-study that resulted in higher education’s gold standard—full accreditation—in 2004. The same year, NCNM conferred 107 Doctor of Naturopathic Medicine degrees and 49 Master of Science in Oriental Medicine degrees, a school record. The accreditation from NWCCU was not only unanimous, said Keppler, the self-study was shared by the commission with Harvard University business and education schools as an example of what can be done when a school is in trouble.

To this day, Keppler, awarded president emeritus status in 2007, is amazed and gratified at the way the entire college pulled together during the crisis. Though he admits he had many sleepless nights, “I was not going to let us fail. I had it in my psyche that nothing was going to stop us. We were going to make it. Failure was just not an option for us.” He added, “I knew I could not do this alone. I knew I needed to get everyone to buy into this if it was going to work. And everyone did buy into it.”

When it was over and accreditation won, the school was truly flying high, he said. “After we were accredited, people took more pride in their ability to do even better; to teach, to do research, and to just be proud of the fact that we were the oldest naturopathic school.”

In 2006, NCNM celebrated its 50th anniversary by changing its name to National College of Natural Medicine in recognition of its key academic programs in the School of Naturopathic Medicine, School of Classical Chinese Medicine and emerging research programs. Said Keppler, it was suggested that the anniversary celebration should be primarily a fundraising endeavor. Instead, he booked a catered lunch cruise on the Portland Spirit for the entire campus community. Some $30,000 in donations came in anyway. When he retired in 2007, the college was solidly in the black and enrollment was near 400 for the first time.

Rise Of Research

Key breakthroughs in the development of Western medical drugs and vaccinations can be tied directly back to plants and natural sources. However, efforts to look more closely at the science of plant-based medicine in Chinese and naturopathic medicine have historically been stymied by lack of foundation and government support. At NCNM there was a strong desire to conduct evidence-based research, particularly by NCNM’s first Dean of Research, the late Anna MacIntosh, ND (’89), PhD; Carlo Calabrese, ND (’83), MPH; and others, but funding and facilities continued to be an issue.

In 2002, Dr. Heather Zwickey was hired as an associate professor of immunology at NCNM and tasked with teaching faculty, staff and students how to do research. Zwickey, whose PhD from the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center was in immunology and microbiology, also studied at the National Jewish Medical and Research Center in Denver, Colorado, before completing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Yale University School of Medicine.

“When I started at NCNM, there were a few people who were enthusiastic about research, but there were no resources available to them,” she said. “Far more people were skeptical about research at a naturopathic school. In their eyes, research had been used to keep natural medicine in the shadows.”

Zwickey added that there was doubt on campus that naturopathic or Chinese medicine could be studied in a randomized, controlled trial model and therefore there would never be an evidence-base to the medicine. “What it meant to me was that we first needed to change the culture on campus. Research wasn’t going to survive if it was just one or two people trying to fan the flame. We needed everyone to be involved in research—everyone to be invested in the successes.” She and other research advocates built community involvement by taking grant applications to every office and classroom to explain the process and give people a chance to comment.

“For the next months while the grant was in review, students, faculty and staff would ask about it. Whether they were conscious of it or not, they had become part of the team. It was little things like this that started to make people less afraid that research was going to be used against them, and more supportive of having research on the NCNM campus.” She added that one of the grants that the NCNM community had gotten excited about was a National Institutes of Health (NIH) R25 Research Education Grant. When it came through in 2007, it “allowed us to really solidify research in NCNM’s culture… This grant provided us the financial support to institutionalize our research culture, train faculty and students, and develop a research degree program at NCNM.”

In 2003, Helfgott Research Institute was founded thanks to a $1.2 million donation from Donald Helfgott. The institute, part of the School of Research & Graduate Studies, (SoRGS), has steadily increased funding and research programs at its site in the former NCNM Natural Health Center on Southwest First Avenue, just down the street from the Lair Hill campus. Today SoRGS has more research faculty and more research projects than any naturopathic medical school. More than 50 students, most of whom are ND candidates, participate in or lead their own research projects with faculty mentors. Ongoing studies include inquiries related to gastrointestinal health, diabetes, nutrition, acupuncture, and global and women’s health, to name just a handful. Significant funding has come from the Murdock Trust, Meyer Memorial Trust and National Institutes of Health. In 2011, the latter funded another four-year round of the grant received in 2007, and in 2015, Helfgott received its largest grant ever, more than $3 million from NIH for complementary and integrative medicine studies.

In addition, reflecting its growing prominence on the research scene, the school and institute maintain a wide array of collaborations with local, national and international organizations, including Oregon Health & Science University, Legacy Good Samaritan, Kaiser Permanente, Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine, University of Washington and Johns Hopkins University.

Stable But Fragile

When David Schleich, PhD, arrived in 2007 to assume the NCNM presidency, he got a gift previous presidents would have loved: a stable financial situation and no serious crisis to handle. A former president of Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine (CCNM) in Toronto, Dr. Schleich was widely known for his scholarship on the professional formation of natural medicine institutions. He had also built CCNM from a tiny school into the largest naturopathic school in North America.

Schleich was already very familiar with NCNM through his research, visits as a guest lecturer, and talks with past presidents, including Drs. Keppler and Jensen. He was also aware of the school’s pioneering status. “NCNM is the parent program of all of them,” he said, noting that many of the founders, deans, teachers, even the core curriculum of the other naturopathic schools in the U.S. and Canada, came from the Portland school.

Schleich said he was also drawn by the fervor and altruistic goals of the students, faculty and staff. However, he said, “I had a real close look at the numbers and I could see that the institution was fragile in terms of revenue streams, equity and its organizational structure. It was stable, but not a situation that would lead to growth easily. And folks were fragile also. They had come through very austere times.”

Drawing on his experience from CCNM, he set out to create an atmosphere where people were willing to take some risk in order for the school to move forward. “We had to change from a culture of caution and scarcity to one of abundance and possibilities,” he said. Schleich and the administration set out to streamline operations such as getting clinic costs under control, and reorganizing medicinary and lab services. He also sought to turn the Continuing Education program into a revenue center, and increase alumni outreach and fundraising activity, all to diversify income beyond the tuition dollars largely generated from the naturopathic program.

Schleich said one of the most significant accomplishments of his tenure was the launch in 2012 of the Master of Science in Integrative Medicine Research (MSIMR) program, through the School of Research & Graduate Studies. There was great apprehension about the program, he said, especially since a certificate program in botanical medicine had recently failed. There were fears that the new program would siphon dollars from the naturopathic program. “It required an act of faith and lots of support from people,” said Schleich. He knew the program would not pay for itself for a few years, but represented a key strategic investment in the expansion of the school’s academic programs.

The risk has more than panned out, and the MSIMR program has served as a template for three additional programs at SoRGS, including a Master of Science in Integrative Mental Health, Master of Science in Global Health, and a Master of Science in Nutrition. In addition, the new graduate programs and the launch of two undergraduate programs in 2016 have been significant factors in enrollment growth since 2007, with record numbers building to 653 students in 2016.

Another highlight Schleich said, was the creation of NCNM’s community institutes beginning in 2012. The institutes, featuring symposia and workshops focused on food as medicine, women’s health, gerontology and herbal medicine, have created revenue and helped raise NCNM’s visibility. Fundraising in the last several years has brought in millions of dollars, he said, including the record $1.35 million donation in 2011 by Bob’s Red Mill founders Bob and Charlee Moore to support nutrition programs. Those donations, coupled with strategic borrowing and utilization of higher education construction bonds, led the college through a string of building acquisitions and remodeling on and near the school’s five-acre Lair Hill footprint. During Schleich’s tenure, faculty and staff have seen significant growth, which was previously very light or non-existent in some areas; along with expansion in key support areas including academic and clinical support, student services, advancement and marketing.

In addition to the school’s expansion and growing reputation, Schleich said that the crowning achievement of his tenure is the granting of university status in 2016, something he feels the school should have done a long time ago. “To aim for university status. I always had that (in mind) from Day One,” he said. He added that the change in status and the rebranding of the school is not just cosmetic, but part of a strategic plan aimed at making the university the “trainer of choice in a variety of professions with a holistic, natural medicine philosophy at the core of it.”

Schleich adds, “Though it is still the case that we have to watch every dollar, we are in growth mode. We’ve added many buildings, we’ve added more property and we’ve added not only programs, but the capacity for even more.” He envisions growth from the school’s current nine academic programs to 17 by 2020, and 35 by 2030. First it will be sports and exercise science, but may one day include bachelor’s and master’s degrees in other healing therapies, and maybe even an MBA in sustainable business practices that can help new graduates, alumni and others in the healthcare field.

He plans a further greening of the campus through the planting of additional gardens and trees, and a new and expanded academic building, complete with underground parking, in one of the present parking lots or near the Min Zidell Garden. Schleich’s future plan includes the gradual acquisition of more properties within the campus footprint. Today, the university has far more equity than it ever has, he said, with a “very healthy” Department of Education financial health ratio of 2.6 out of a possible 3.0. “The future is friendly,” he often likes to say. But now he adds with a little smile: “NUNM will be here long after you and I have departed the planet. We just have to stay the course and stick to the knitting, as the saying goes.”

Bright Future

Said Bill Tribe “I don’t think those of us who were there (at the beginning) thought it would get to this so quickly. The number of people involved, the money involved, I’m quite surprised at how well we are doing now. I don’t think the school has ever been on firmer footing, and NUNM and the profession will continue to grow and become even better.”

Melanie Henriksen, ND (’05), MSOM (’05), MN, dean of the College of Naturopathic Medicine, still the largest student group at NUNM, sees a bright future for the ND college, the university and the naturopathic profession. She cites the recent top-to-bottom ND curriculum redesign as one of the highlights of her career and feels, “The program that we have developed aligns very well with provider needs for the future and our students’ strong desire to be involved in an interdisciplinary healthcare system.”

John Weeks, the noted editor of the Integrator Blog and a complementary and integrative medicine policy guru, would agree. During a keynote address in 2015 at NCNM’s commencement, he said the school deserves the “Mothership” moniker because its people have been warriors, not only for advocating the whole person, individualized care approach, but also for sparking discussions from the community to the federal government that are changing the medical landscape “from sick care to health care.”

NCNM grads and their allies years ago realized they needed colleges, accrediting agencies, standardized licensing exams, licensing in new places, and federal government recognition of the accreditors, he said. “They figured out what the strategic choices were, applied themselves to getting it done, and got it done.”

He added, “We have come a long way. We are now entering zones where we are not fighting for our lives, but are now invited in to be the foundation” of a new healthcare system. The momentum toward holistic and integrative medicine, he said, “is the momentum we have all been working for all these years.”

As Dr. Ken Peterson, one of the original NCNM faculty members, put it in 2010: “When we started, we were very unpopular, regarded as quacks. Now the world is beating a path to our door.”